As defined by the Institute of Food Technologists (IFT, 1975), sensory evaluation is “a scientific discipline used to evoke, measure, analyze, and interpret reactions to those characteristics of food and materials as they are perceived by the senses of sight, smell, taste, touch, and hearing”. Food sensory evaluation is a structured and systematic approach to gathering information about how food products are experienced through the five senses: taste, smell, sight, touch, and sound.

This process is essential in the food industry for developing and marketing new products, enhancing current offerings, ensuring quality, and maintaining quality certifications (ex: SQF quality code). Sensory evaluation employs both qualitative and quantitative methods to align products with customer expectations and preferences.

Let’s review how the 5 senses can be utilized to manufacture and market successful food products.

How can we use the five senses to evaluate food?

We know the five senses – touch, sight, hearing, smell, and taste. When applied to food and beverage evaluation, each sense plays a role in assessing sensory characteristics that inform product development, marketing, quality control, and optimization.

For example, our sight helps us judge the color and appearance of food, which significantly influences our perception of flavor and quality. Flavor itself is understood through taste and smell: taste buds on the tongue detect taste, while smell receptors in the nasal cavity process odors.

The five basic tastes are bitter, sweet, sour, salty, and umami (savory and meaty flavor detected by specific taste receptors on the tongue). Food evaluations also consider sensations like spiciness, cooling, and tingling, known as chemesthesis, which are processed by the trigeminal nerve to signal potential irritants like alcohol, menthol, and vinegar.

Sensory researchers study food aromas in two ways. Smell is first perceived directly through the nose; then, when we chew, odor molecules reach the nasal cavity (a process called retronasal olfaction). This dual aroma experience is crucial for studying flavors. A classic exercise to demonstrate this involves eating a jellybean with your nose held, only releasing it to fully recognize the jellybean’s aroma.

Take the evaluation of wine, coffee and tea as examples. In sensory tests, panelists sniff and sip these beverages, detecting tastes, aromas and other attributes like tannin astringency, temperature, and heat from alcohol or spiciness. Each aspect of taste, smell, and chemesthesis contributes to the definition of product flavor.

Another aspect of food sensory evaluation is human subjects and their varying sensitivities to different molecules. A good example of this is our sensitivity to PROP, a bitter compound.

Sensitivity to 6-n-propylthiouracil (“PROP”) is a marker for the population. Around 20% of the population is very sensitive to PROP and 30% cannot taste it. People’s innate ability to taste bitter foods such as caffeine and quinine may affect their food preferences and diet. Depending on the objectives of a sensory test, the PROP test can be used to screen and select panelists.

Human sensory responses are both innate and learned. Babies are naturally inclined to sweet and umami tastes but averse to bitterness. In contrast, aroma preferences develop with experience, allowing us to cultivate tastes for specific scents or flavors over time.

Scientists and consumer researchers also study taste adaptation and the concept of taste sensitization and desensitization. For instance, we can get used to the spiciness or saltiness of foods. We can also become desensitized to it and lose tolerance to spiciness in food.

Sensory science also considers touch and texture. For instance, eating a chip involves feeling its hardness and crumbly texture, both by hand and in the mouth, which influences enjoyment. Even sound, such as a cereal’s crunch or a cork’s pop, can signal quality and freshness.

Visual appeal, particularly color, greatly influences consumer choices. The phrase “we eat first with our eyes” holds true, and food assessments sometimes involve blind testing to eliminate visual bias.

How do we conduct a food sensory evaluation?

Sensory evaluations must be carefully controlled to avoid sensory biases. Factors like lighting, time of day, and serving order can affect perception. Panelists, especially those with taste or smell impairments (anosmia and ageusia), should be screened to ensure valid results.

Assessors can misidentify sensory perceptions due to psychological factors. Expectation, stimulus and logical errors are common biases that taint sensory judgement. The sensory scientist will therefore be careful to prepare food in a kitchen, out of sight from the panel so as to not reveal product information or test objectives. A good sensory panel is impartial, discriminant, motivated and able to follow test instructions.

In sensory tests, trained or untrained panels are recruited depending on the study’s goals. Large consumer panels (100+ participants) are typical for general preference testing, while descriptive analyses use trained panels to generate detailed profiles of food sensory attributes. Various tools, such as the 5-point or 9-point hedonic scales, help measure consumer acceptance, liking and preferences. Descriptive panels require intensive training and often use scaled descriptors to rate sensory characteristics precisely.

In consumer studies, panels – generally heavy users of the product – rate their liking for products without specific training. Meanwhile, trained panels in descriptive studies assess detailed sensory attributes, and data from both consumer and trained panels can be combined to understand product acceptance more fully.

Evaluations aim to measure food acceptability, either by identifying differences between products or determining whether a product meets specific standards.

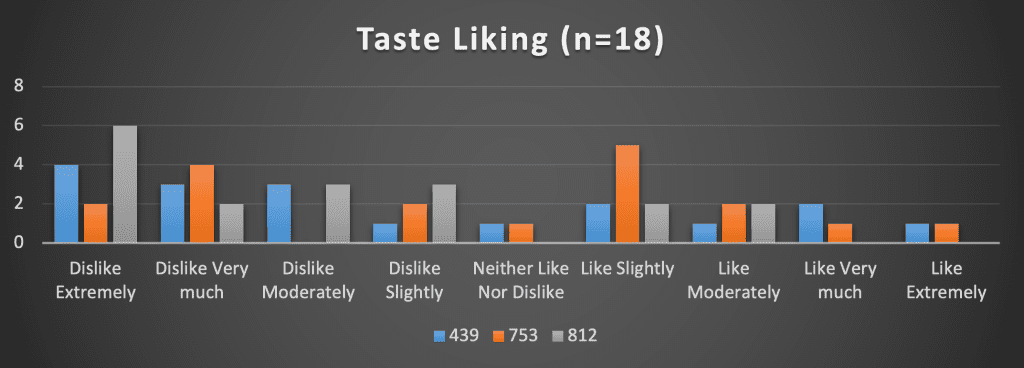

Consumer test using the 9-point hedonic scale (18 students assessed 3 food products “blind” for taste preference). Frequencies of liking for products 439, 753 and 812 are tabulated and graphed.

What is a food sensory evaluation test, and how do we assess taste?

A sensory food evaluation test is conducted to assess the quality of a product, define its sensory profile for comparison with similar items, or measure consumer preference. Additionally, these tests can study human sensitivity to specific compounds or “thresholds”.

In sensory science, when establishing the sensory profile of a food or beverage, panelists act as “human instruments” and undergo calibration through training. However, extensive panel training is not always required for certain tests. For example, discrimination tests are used to identify whether an overall difference exists between two products or if they are perceived as identical, while consumer tests gather information about how much people like a product (hedonic data).

In both cases, it’s crucial that panelists can perform a food sensory evaluation accurately, as sensory acuity is necessary to obtain valid results. Screening is also essential in consumer sensory research to ensure the panel represents the right consumer group and to identify what drives product liking, with the goal of fostering repeat purchases.

For descriptive sensory ratings, more precise analysis is needed to capture a food’s sensory descriptors accurately, enabling foods to be categorized, ranked, and differentiated. These descriptors can have varying intensity levels, so it’s essential that panelists are not only accurate but consistent, reproducible in their understanding and rating of these sensory attributes.

Descriptive evaluations may compare products on either absolute or relative scales. For instance, in quality or product grading, absolute ratings help establish if a product meets certain sensory standards.

Training panelists often includes sensory reference samples to ensure a unified understanding of sensory concepts, while scaling techniques are used to rate intensity. Depending on the method, training can last anywhere from 30 to over 100 hours, with quicker methods still requiring some level of training.

How is food acceptability measured?

Food acceptability can mean either a lack of detectable difference between two batches made under the same conditions (e.g., duo-trio discrimination test) or that a product meets a sensory standard when evaluated alone (e.g., descriptive test with defect absence). It can also refer to favorable consumer ratings, often measured with a hedonic scale.

Food acceptability can mean either a lack of detectable difference between two batches made under the same conditions (e.g., duo-trio discrimination test) or that a product meets a sensory standard when evaluated alone (e.g., descriptive test with defect absence). It can also refer to favorable consumer ratings, often measured with a hedonic scale.

What is the 5-point hedonic scale?

The 5-point hedonic scale, along with the 9-point scale, is a common tool in consumer research for measuring product liking. In these tests, consumers taste products and rate their preferences, typically without sensory training.

These tests don’t aim to create a detailed sensory profile but instead focus on overall preference. In contrast, descriptive assessments with trained panelists are used to identify the drivers of liking. Combining hedonic data with descriptive data through preference maps can reveal insights about product acceptance and consumer preferences.

How are sensory evaluation panels used in food testing, and what methods are involved?

Food sensory evaluation panels can include trained or untrained panelists, depending on the test’s objectives. Consumer tests usually require a large panel size (100+ people) to identify taste preference clusters among frequent users.

In a sensory lab, descriptive panels are used to accurately characterize a product’s sensory attributes and compare it to a reference. These panelists receive extensive training, including sensory references, to rate the intensity of descriptors using scales. Descriptive methods may include both quantitative and qualitative approaches, depending on the specific sensory attributes being measured.

References

Genetics of Taste and Smell: Poisons and Pleasures – PMC

When visual cues influence taste/flavour perception: A systematic review – ScienceDirect

Effects of capsaicin desensitization on taste in humans – PubMed

PTC/PROP Taste Strips – Complete Set – Sensonics International

Savory Science: Jelly Bean Taste Test | Scientific American

Sirocco Food + Wine Consulting provides sensory training and consulting services. We have conducted many sensory tests on products like wine, chocolate, dairy and plant-based products as well as fish. Examples of sensory evaluations are presented in our blog. Our principal and founder, Karine Lawrence, is UC Davis trained. We collaborate with Tastelweb, a French sensory software company. Contact us to discuss your project and request a quote.